Few Britons made a greater impact on the history of the twentieth century than Winston Churchill. He is known as the man who led the fight against Nazism and was victorious, defended Western liberal democracy and later, in the Cold War years, proved his diplomatic strength against leaders such as Stalin.

Even before the events of 2020, historians and critics have sought to shed light on the more uncomfortable and controversial aspects of Winston Churchill as a political figure and war hero. Fervent support for British imperial rule and general comments which suggest a white supremacist attitude have emerged as difficult aspects of the leader.

Churchill’s attitude and actions towards the Indian subcontinent have been highlighted as some of the most troubling aspects of his legacy.

There were crippling rice shortages and survivors described begging neighbours for some form of nourishment.

In the early 1940s, a disastrous famine devastated the north-eastern region of Bengal. Churchill had recently formed the wartime coalition in Britain and was appointed Prime Minister by King George V on May 10th 1940. Churchill was tasked with leading the alliance to victory. Thus, when a famine broke out in Bengal, perhaps it was not in Churchill’s interest to divert British resources from the war effort towards the region, despite the fact that South Asia was one of Britain’s most valuable colonial assets at this time.

Critics have suggested that Churchill’s wartime policies exacerbated the famine by diverting resources, such as grain and rice, out of India for the Allied war effort. There were crippling rice shortages and survivors described begging neighbours for the starchy rice water for some form of nourishment. It is estimated that around 2 million people died due to the famine in the year 1943 alone.

It is estimated that around 2 million people died due to the famine in the year 1943 alone.

Churchill’s attitude towards the famine revealed how he viewed non-white imperial subjects. In telegrams, Churchill blamed the famine on Indians themselves, stating that it would have been less severe had Indians not been “breeding like rabbits”. In addition, according to historian Pankaj Mishra, when implored by British representatives of the empire in India to mitigate the famine by sending food, Churchill replied by asking why Gandhi hadn’t died yet.

The extent to which British actions directly impacted the famine has been debated; according to Mishra, it was a “combination of war and mismanagement”. It is important to note that the Second World War, like the first, was a war characterised by imperial power and domination. Churchill, it seems, sought to defend these values by any means necessary.

When implored by British representatives of the empire in India to mitigate the famine by sending food, Churchill replied by asking why Gandhi hadn’t died yet.

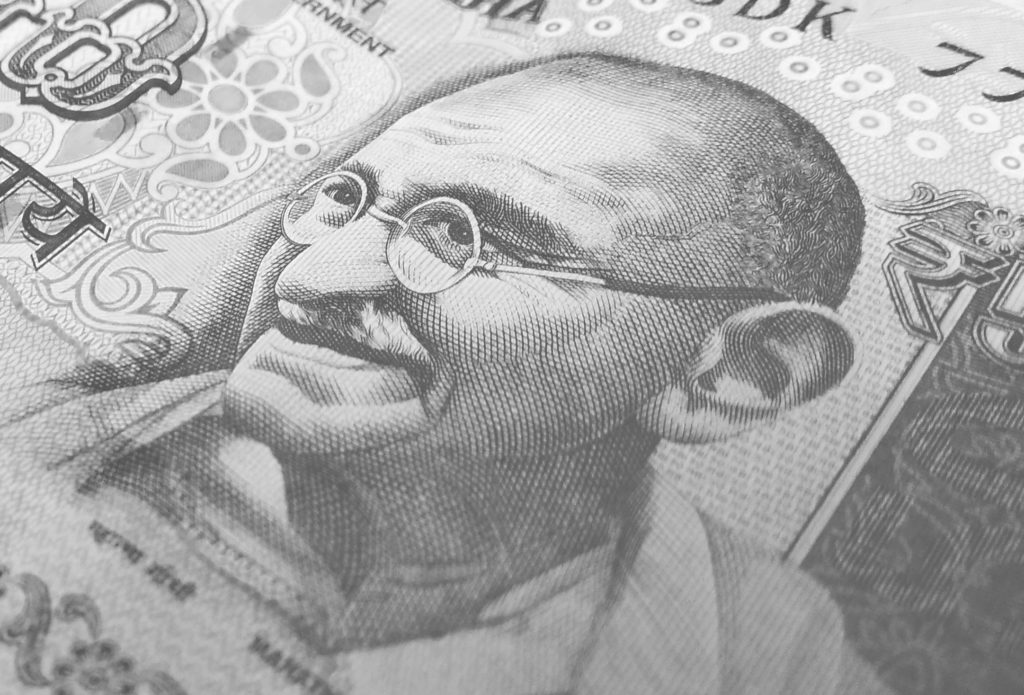

Churchill saw Gandhi as a persistent challenge to imperial rule and was outspokenly critical of him throughout his political career. While Churchill was a defender of the values of empire, the great spiritual leader Gandhi devoted his life to peacefully challenging British imperial rule through the method of passive resistance (satyagraha). His non-violent ideology and peaceful methods of politics, such as fasting and organised marches, provided a powerful moral indictment of British rule, and he continues to be revered in India and globally. Critics in the Indian press were deeply insulted when Churchill suggested in his war memoirs The Hinge of Fate in 1951 that Gandhi had taken glucose supplements while fasting. Louis Fischer wrote in his acclaimed biography of Gandhi that the two leaders had diametrically opposing outlooks: “To Churchill, all Indians were the pedestal for a throne. He would have died to keep England free, but was against those who wanted India free.”

There is evidence to suggest that Churchill, as part of the British imperial project, stoked religious tensions to encourage India to enter the war. India had not entered the war by 1942, following the failure of the Cripps Mission. On 8 August 1942, Gandhi launched the Congress Party’s “Quit India” campaign, calling for British imperial rule to end. This was met with swift repression from the British government, with tens of thousands imprisoned, including Gandhi and Nehru. During this time, with Congress leaders imprisoned, Churchill encouraged Jinnah to bolster Muslim nationalist sentiments. Churchill has been seen as a critical figure in the creation of Pakistan.

Hindu-Muslim rivalry continues to mark conflict in the region. In parts of Pakistan, Islamic fundamentalist sentiments continue to rage, while in India, Hindu nationalism has been given renewed vigour under Narendra Modi.

Recognising Churchill as a war hero and coming to terms with his difficult racial and imperial legacy are not mutually exclusive.

Churchill’s views and actions towards peoples in the Indian subcontinent are just one aspect of his imperial legacy. Often, his language conveyed a general sentiment of white supremacy.

His views should be contextualised in the period of formal British imperialism. Churchill is a statesman of this period. He led a global imperial power during the Second World War, after which formal decolonisation took place and the British empire was gradually dismantled.

Recognising Churchill as a war hero and coming to terms with his difficult racial and imperial legacy are not mutually exclusive. We must face uncomfortable truths about a man who has been revered in Britain for decades.